Long before I knew anything about pivot charts or data science, I wondered what it would be like to use a spreadsheet in three dimensions.

How powerful would it be to correlate data points across more than just an x-y axis? When searching for such a solution, I was constantly told that pivot charts were what I was looking for. This isn't true, since pivot charts are re-aggregations of existing 2-dimensional data. No, what I wanted was a way to visually organize data on more than two axes without grouping them.

Later, I learned there were indeed 3-D plots of data. But thanks to the limits of human cognition, that's kind of where we stop. It's not like we can usefully conceive of a four-dimensional plot, can we? In part, that's where ML comes in, identifying trends and patterns across an arbitrary number of dimensions—or "features," to use the lexicon of the discipline.

Still, wouldn't it be cool to have, like Tesseract Mode in Excel? Maybe I'm just a weird nerd about data.

Note: I am definitely just a weird nerd about data.

When I'm pulled into conversations around the nature of true positives and false positives in cybersecurity, I often feel as though I've fallen into Edwin Abbott's Flatland

Here I am, a being of dimensionality, capable of perceiving height, width, and depth, when suddenly I'm surrounded by these barely-visible creatures yapping about "False positives" and "Type 1 errors."

My dear shapes, there's so much more to the story. It's time to retire the binaries in favor of a more nuanced view of detections.

The Value of Classification

A classification only has value insofar as it can describe the efficacy of our tools and processes. But "success" for a tool and a process are by no means the same thing. An intrusion detection system succeeds when its rules trigger appropriately and with minimal noise. A process succeeds when a potential incident is brought to resolution—whether the alerted item was malicious or benign. A successful detection may well be benign in nature (I have an entire website of these phenomena). How should these be described? A "false positive" connotes failure of detection, when in fact the rules as stated performed flawlessly.

"But Taggart, rule tuning should be able to prevent false positives!"

Hoo boy, "should" is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that sentiment. The overlap space between malicious and benign for many activities is nearly a perfect union. Without correlation, it is simply not possible for atomic detections to dispositively establish malice. Consequently, all we have left for the detection component of an "incident" is whether the rule successfully detects obvious malicious activities of that type. This is not particularly helpful by itself.

Possible Outcomes

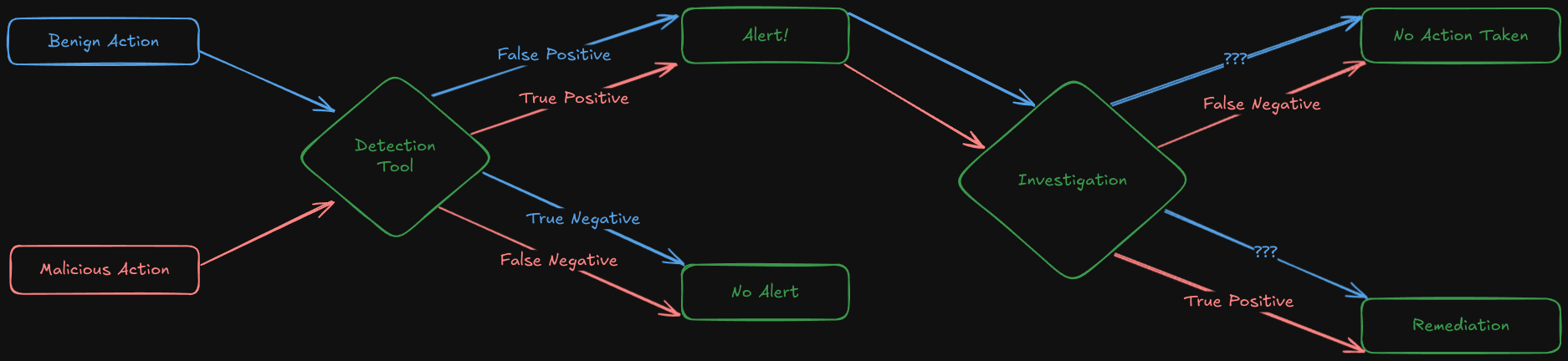

Let's imagine an entire "incident," from an alert in a detection tool, through incident response and investigation, through final disposition. Considered as a system, what are the possible states?

From a game theory standpoint, our four outcomes are not that interesting: true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative. No surprises there. What's interesting here is the transformation that can take place during an investigation.

The pathway for malicious activity is clear, even if the final dispositions' meanings are not. A confirmed malicious action/artifact that is remediated is true positive; a properly alerted malicious action/artifact that is judged benign by investigators is a false negative (note that this discrepancy is not captured by the final disposition). After that, things get a little murky. What would an alerted, investigated, "remediated" (investigators causing needless impact) alert be? If it's a "False Positive," why was action taken?

And what about alerted, benign items in which no action was taken? Is that also a "false positive?" If so, what is captured about the decision of the investigators, who correctly identified the activity/action as benign, even when the alerting tool did not. From a purely investigative standpoint, that is a "True negative."

And at the end of the day, we label this entire process with one of four values.

I don't think this adequately tells the story of what happened here. Here's what that single 4-variant value doesn't contain:

- Was the incident alerted?

- Did the alert result in investigation?

- Was the action benign?

- Did remediation occur?

- Did the IR team get it right?

This loss of fidelity is expected in projection—representing n dimensions in n-1 dimensions. Think about drawing a cube on a piece of paper. In 3-D space, the corners are all right angles. But if you measure your drawing, you won't find any right angles—unless you drew the cube head-on, in which case congrats, you drew a square.

I'm all for simplicity and succinctness, but too much is getting lost in the reduction here.

There are solid examples of alternatives.

The Admiralty System

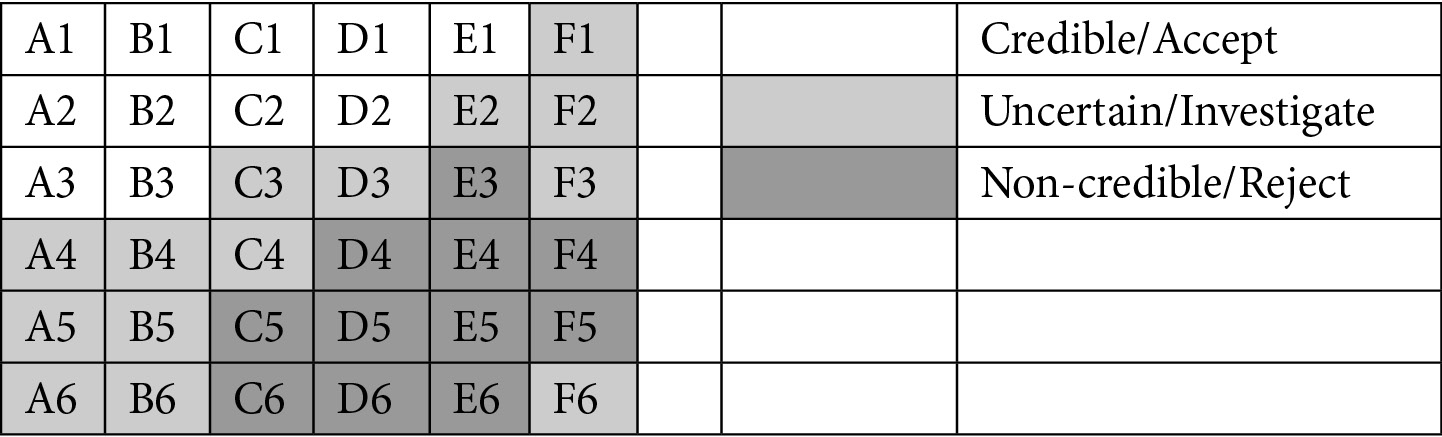

The Admiralty Code, or the NATO System, is used for evaluating the reliability and credibility of gathered intelligence items. Both factors—reliability and credibility—are given a rating on a scale of 6. For credibility, letters are used. For reliability, numbers. You put these together, and you get an interesting matrix of action recommendations on the intelligence.

Credit: Operationalizing Threat Intelligence, ⓒ Packt Publishing

Again, dimensionality rears its head. Look at what emerges when we plot these two axes: a much richer understanding of the intelligence item.

Now, reliability and credibility are not the values we care about for an incident, nor do I think six values make a lot of sense for our outcomes. I'm pointing to the Admiralty Code as an example of balance between nuance and brevity.

What might such a system look like for detection/incident response?

I have some thoughts.

The Incident Response Rating System

Our goal is to tell the story of the alert/incident, to move away from the tyranny of the false positive. We will therefore avoid that language in our new description of an incident, although our descriptions may imply these outcomes. Instead, we seek to answer the following questions:

- Was the event alerted?

- Was it alerted correctly (proper detection engineering)?

- Was the alert investigated?

- Was the activity/artifact remediated?

- What was the final disposition determined by the incident response team?

Our story appears to have three acts: Detection, which is in the hands of automated alerting tools; Response, belonging to the IR team; and disposition, which is the retrospective summation of the event.

The varying lengths and pathways of the story do not map well onto a grid, as the Admiralty Code does. That was a demonstration of the value of dimensionality, but we need something different for this use case. Perhaps something close to the CVSS Vector, which encodes vulnerability details in a human-readable shorthand to provide deeper context than a simple CVSS score 0-10.

Following that "vector" notation, we can shorthand the Detection component this way:

D:A+: Detection correctly alertedD:A-: Detection incorrectly alertedD:N+: Detection correctly did not alertD:N-: Detection incorrectly did not alert

For non-alerting detections, the story stops there. But for alerted rules that are passed to incident response, we need to consider those actions. We'll describe them this way:

R:I+: Incident investigated, remediatedR:I-: Incident investigated, not remediatedR:N: Incident not investigated (no+/-because remediation is not possible)

We need a separator between detection and response. CVSS vectors use slashes, which will do fine here.

Finally, our final disposition: benign or malicious? We'll append that to the vector with a B or M and two colons for an offset.

Here's what that looks like all together.

D:A+/R:I+::M: Detection correctly alerted, investigated, remediated; malicious- "True positive"

D:A+/R:I+::B: Detection correctly alerted, investigated, remediated; benign- Rule needs tuning and the IR team caused undue impact

D:A+/R:I-::M: Detection correctly alerted, investigated, not remediated; malicious- IR team failure

D:A+/R:I-::B: Detection correctly alerted, investigated, not remediated; benign- "False positive"

D:A+/R:N::M: Detection correctly alerted, not investigated; malicious- IR team failure

D:A+/R:N::B: Detection correctly alerted, not investigated; benign- "Known false positive" based on alert evidence

D:A-/R:I+::M: Detection incorrectly alerted, investigated, remediated; malicious- Revisit the rule; maybe it's better than we thought

D:A-/R:I+::B: Detection incorrectly alerted, investigated, remediated; benign- Bad rule tuning and the IR team failed to correctly disposition

D:A-/R:I-::M: Detection incorrectly alerted, investigated, not remediated; malicious- Systemic failure

D:A-/R:I-::B: Detection incorrectly alerted, investigated, not remediated; benign- Rule needs tuning

D:A-/R:N::M: Detection incorrectly alerted, not investigated; malicious- The rule found something useful but the IR team did not

D:A-/R:N::B: Detection incorrectly alerted, not investigated; benign- Known bad rule; tune if possible

D:N+::M- Impossible; you're missing a rule

D:N+::B: Detection correctly did not alert; benign- "True negative"

D:N-::M: Detection incorrectly did not alert; malicious- "False negative"

D:N-::B- Impossible; benign activity should not be alerted

That's a lot of variations! Look how weird and asymmetric this all looks when "projected" into these dimensions. Look how much we were masking with "True/False positive/negative."

This is a deeply imperfect solution, but I do think it creates the desired middle position between oversimplification and a complete incident report.

Take it, play with it, amend it, do whatever. This is just a blog post, not a standard.

Unless...?

Nah.